The Jet Engine and Sir Frank Whittle

The Museum houses a unique collection in the Sir Frank Whittle Jet Heritage Centre, of aircraft, engines and supporting exhibits illustrating the fascinating story of the jet age. The story of Whittle's jet engine is told in pictures, video and artifacts including an animated display.

On the 15th of May, 1941, the first British jet-powered plane took off from RAF Cranwell on a historic 17 minute flight. The jet age had begun! The man who made it possible was Coventry-born engineer, Sir Frank Whittle. From an early age Whittle had been more interested in engines and aircraft than anything else and soon decided to join the RAF. Whittle's family were of modest means and he could not afford to enter the RAF College at Cranwell, so attempted to enter as an apprentice. He failed, being too short and thin to pass the medical. Aged only 15, Whittle was determined that this would not stop him so he exercised until he gained three inches in height and filled out a bit more. He reapplied in 1923 and didn't mention his previous application - and this time he was successful.

In 1926 he was selected for officer and pilot training. During his time at Cranwell he wrote his thesis, entitled Future Developments in Aircraft Design. In this he first mentioned the possiblities of other forms of propulsion for aircraft. Later he came up with the idea of using a gas turbine to produce jet propulsion. He tried to interest the Air Ministry but they felt it was impractical. Despite this Whittle filed a patent application. By 1932, during which time he had been selected to specialise in engineering at RAF Henlow, the patent was granted. Incredibly no-one thought it important enough to keep within the UK, and it was published in many countries, including Germany (research on jet engines began in Germany a year later). Whittle made attempts to drum up interest within private industry but got nowhere.

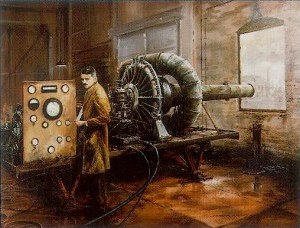

painting by Rod Lovesey

Everything changed in 1936, when with the help of two ex-RAF officers and an engineer, with funding from an investment bank (O. T. Falk and Partners), the company of Power Jets Ltd. was formed. Based in the British Thomson Houston works at Rugby, work proceeded slowly - Whittle was still a serving RAF officer and support from the Air Ministry was non-existent. But on the 12th of April, 1937, the first run was made of the Whittle Unit (WU). Onlookers ran for cover amidst a "noise like an air raid siren" but the idea was proved. In the meantime, the clouds of war were gathering on the horizon, but still the Air Ministry was not interested, concentrating on more conventional designs for aircraft and engines.

With the outbreak of war in 1939 the Air Ministry finally became interested and Power Jets was given a contract to produce an engine for use on a real aircraft. Gloster aircraft got the contract to build an aircraft around the engine; the E.28/39 would be that aircraft. While development continued on a useable jet engine, Whittle still had to battle with the authorities - during the Battle of Britain, the National Academy of Science's Committee on Gas Turbines reported:

In its present state, and even considering the improvements possible when adopting the higher temperatures proposed for the immediate future, the gas turbine engine could hardly be considered a feasible application to airplanes mainly because of the difficulty in complying with the stringent weight requirements imposed by aeronautics.

The present internal combustion engine equipment used in airplanes weighs about 1.1 pounds per horsepower, and to approach such a figure with a gas turbine seems beyond the realm of possibility with existing materials.

Whittle would later say "Good thing I was too stupid to know this"! The constant fighting for support took its toll on Britain's efforts to get a jet aircraft in the air, however. The Germans, using a jet engine designed by Von Hain, had the Heinkel 178, a rather ramshackle affair using an axial flow turbojet (unlike Whittle's centrifugal flow design), in 1939 and the Italians just about managed to get the hopelessly underpowered Caproni-Campini N.1 into the air in 1940 (more of a pseudo-jet as it used a piston engine buried in the fuselage to power a turbine).

The E.28/39, sometimes known as the Pioneer or even Squirt, was powered by Whittle's W.1 engine and first flew on 5th May 1941, piloted by test pilot Gerry Sayer. Finally the Air Ministry realised the potential of the new powerplant and plans for a jet fighter were made. This would be the Meteor, also to be built by Glosters. But now Whittle had another battle on his hands - to keep control of his invention.

Kenneth C. Aitken AGAvA

available from the museum shop

The aircraft industry was worried about the new invention and desperately wanted to get involved despite their earlier lack of support or interest. Pressure brought to bear on the government resulted in Rover being given the contract to produce the W2 engine for the Meteor. With no experience in gas turbines, Rover quickly fell behind schedule and in 1943 Rolls-Royce were called in to replace them. With much aero engine experience, Rolls-Royce did a better job, but development should have been left to Whittle and Power Jets, who really knew what they were doing. The plans for Whittle's designs had also been handed over to the Americans, who built copies for use in the experimental P-59 Airacomet. Whittle worked with the Americans to help them and was impressed with the level of enthusiasm they showed - and remarked on how things would have been different if he'd had that level of support from British industry. Meanwhile the time and effort wasted meant that the Meteor did not fly until 1943 and was not ready to enter service until 1944.

The Meteor would never see combat against its German contemporary, the Me-262; partly because Hitler had decreed that the Me-262 should be used as a ground attack aircraft instead of a fighter! 616 Squadron held the honour of being the first British unit to operate a jet powered aircraft, and notched up their first victory in August flying their Meteors against V-1 flying bombs.

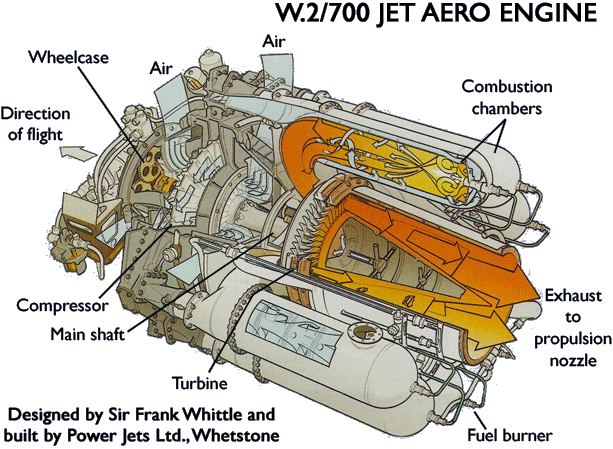

Work had also begun in 1942 to develop a supersonic aircraft using an augmented (afterburning) W.2/700 engine of much greater power - the Miles M.52. In late 1944 the government gave away much of the data on the high speed aerodynamics to be used on the M.52 to the Americans who were developing a similar but rocket-powered aircraft, the Bell X-1. After the end of WWII, the new government then cancelled the M.52 project just months before the first prototype was due to fly citing safety and cost reasons.

Work on the augmented W.2/700 engine stopped and Power Jets was nationalised and merged with the gas turbine section of the Royal Aircraft Establishment to form the National Gas Turbine Establishment. Whittle and most of his team resigned in disgust. It was the end for Power Jets (the old Power Jets' site at Whetstone is still in use today; the power generation division of GEC Alsthom is situated there and the old cooling pond is still utilised).

Incredibly, having given away the plans for the jet engine to the Americans along with much of the Miles M.52 research, the new government gave Rolls-Royce jet engines to the Russians as well, resulting in the quick development of the MiG-15 fighter aircraft. The stress of his constant struggles for support had led to a deterioration in Whittle's health and eventually in 1948 he retired on medical grounds. In his post-RAF career Whittle continued to work on gas turbines and then drilling machines, in particular working for Shell, filing several patents related to drilling equipment. He also advised the aviation industry (including BOAC and Bristol Siddeley) and later he moved to the US - his experience there during the war had showed him an atmosphere of openness and easy recognition of a person's achievements and this no doubt influenced his decision. His final work was as a research professor at the US Naval Academy.

In 1981 Whittle wrote a book titled Gas turbine aero-thermodynamics, often regarded as the 'bible' in that field. In 1986, Sir Frank was recognised by the establishment in a much more generous and open manner - he received the Order of Merit from the Queen. Sir Frank died on August 1996 at the age of 91. The museum's Sir Frank Whittle Jet Heritage Centre stands as a tribute to Sir Frank, the father of the jet age and the man who made the revolution in passenger air travel possible.

Coventry city centre

We have an unrivalled collection of original archive film and other material relating to the development of the jet engine; some of our film has been used in television documentaries including the BBC's Horizon programme. We also have extremely rare colour film of early Meteor operations with 616 squadron.

The local area also pays tribute to Sir Frank's genius, with a statue of the great man standing under the 'Whittle Arches' sculpture outside the Coventry Pool Meadow Bus Station (near the Transport Museum) and a local school being named after him (The Sir Frank Whittle Primary School in Walsgrave). Slightly further afield in Lutterworth a replica of the E.28/39 has been erected on a roundabout on the A246 road and a bust of Sir Frank is on display the War Memorial. Another E.28/39 replica can be found on a roundabout in Farnborough along with one at the Jet Age Museum at Staverton. Various roads and buildings throughout the country also bear his name.